How would you best organize your work environment for maximum productivity if you were tasked to develop a type of application you had never developed before?

Wouldn’t it be nice if you could witness how an experienced developer manages the tools of the craft so that you could draw ideas and incorporate them into your own workflow?

This post aims to answer the above for the type of work I do by sharing how my workflow looks like. I want to compel you to share your own story in the comments section, and by doing so, create a collection of stories so that others can benefit from them.

Development workflows are like colors: each programmer has their favorite and their favorite is not gonna change easily based on others’ preferences.

That said, even though every developer has their own workflow, there are developers that do not yet have an established workflow or whose workflow is not suitable to the kind of work they do.

I witness individuals with workflows not really suited to the task they are trying to accomplish over and over again, especially when mentoring young interns or even new hires. It is true that such individuals will end up shaping their workflow to better adapt to the project work at hand but I suspect they’d be better off by witnessing how their peers currently do work and adapting their practices accordingly. (Case in point: I can picture some of our interns when they had “a-ha!” moments after seeing how their hosts managed routine work.)

With that spirit in mind, this post presents what my current development workflow looks like, which is adapted purely for working on remote machines and on developing console-based applications.

History of my workflow

Over the many years I’ve been coding—more than 20 at this point <insert horror face/expletive here>—I have gone through many different workflows. But on 2007 the churn stopped and, since then, I have stabilized on a relatively simple workflow that I still use to this day.

What happened in 2007? My undergraduate project, which required me to work directly on a remote machine—a PlayStation 3 running Fedora, if you must know. My previous approach of using a local graphical editor with multiple terminal windows spread out throughout various virtual desktops did not play well with such remote work. (X forwarding? No thank you.)

Such change in circumstances made me start using SSH exclusively to remotely edit and compile code. I must confess that doing so was oppressing at first: the feeling of not being able to escape the terminal was claustrophobic, and it felt that way because the change in environment slowed the typical edit/build/test cycle considerably.

Practice makes perfect though. Weeks, months, years passed and I got used to that workflow, particularly because my need to access remote machines instead of just doing local development increased. Over the course of the years since, I have refined and stuck to the same workflow.

I have to confess that, in various occasions, I have attempted to go back to a more graphical-oriented environment but have been “unable” to do so. Existing practices and muscle memory are truly hard to break at this point. A coworker of mine has the theory that we spend many of our first years with computers tinkering nonstop with our environment until we reach a sustainable point, possibly due to wear or boredom, and then introducing any major change is really hard due to friction. Sounds plausible.

Anyway. History is in the past so let’s get to the details.

Enter tmux

tmux, which stands for Terminal Multiplexer, is the tool you must master if you ever want to be proficient at the console. (There also is GNU Screen if you’d like, but tmux is just better.) Tabbed terminal emulators, like the Gnome terminal or OS X’s Terminal, are a good complement to tmux but not a replacement; we’ll see why later.

As its full name implies, tmux allows you to manage multiple virtual terminals within the same terminal emulator. In other words, tmux makes it possible to run more than one program at once and to display all those running programs in different layout combinations: side by side, overlapping windows, etc. all managed via the keyboard.

tmux groups running applications in sessions. Each time tmux is invoked, a new session is created and new applications can be started within it. The real power comes from knowing that sessions can be detached and reattached to different terminals at will because sessions live on the server and are not tied to the terminal that started them.

Beginner tip

If you are just getting started with tmux or Screen, remap the default command key before you build muscle memory around it. By default, tmux uses Ctrl+B and Screen uses Ctrl+A. Unfortunately, these keys conflict with standard keystrokes used in Emacs and readline-based command-line editing, which will get in your way if you are used to these shortcuts.

In my case, I chose Ctrl+J years ago as a replacement because this particular combination of keys did not seem to interfere with any other common keybinding—and have not found any conflicts yet during the years.

For tmux, add this to your ~/.tmux.conf:

set-option -g prefix C-j

unbind-key C-b

bind-key C-j send-prefix

Project directories

As it may be obvious, I store each project in its own directory. The key here is that “project” does not equal “software product”: herein, project means the active development work of a specific feature or bug fix for a given software product. Therefore:

- For projects whose upstream product is managed by a distributed version control system like Git, the local directory may hold more than one project at a time by means of lightweight branches. If this is bothersome, I can just create multiple clones of the remote repository, one for each project.

- For projects whose upstream product is managed using a more traditional centralized version control system, I check out separate copies of the repository for each project I might be working on.

I store all projects under ~/os/, which used to stand for “Open Source” but at this point is just a synonym for “source trees” or “projects”. For example, I have a ~/os/freebsd/base/head/ directory and a ~/os/freebsd/base/stable/10/ directory to hold FreeBSD’s source tree at HEAD and stable/10 respectively, a ~/os/pkgsrc/ directory to hold pkgsrc’s CVS checkout at HEAD, and a _~/os/kyua/_ directory to hold Kyua’s Git repository copy with its multiple local branches.

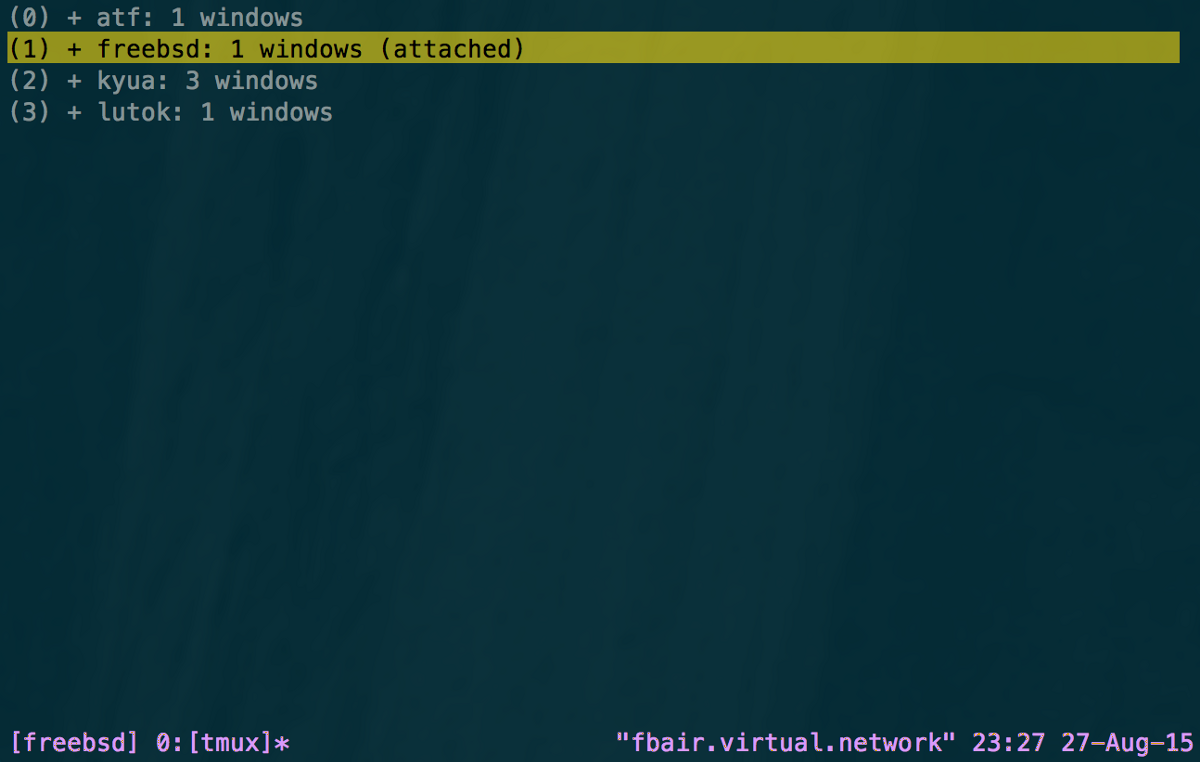

Managing sessions

With this layout, I have a script in my path called open-session.sh which takes a “session” name, aka a project name, and opens a tmux instance within the directory of the project. If the session is already open, the script detaches that session and attaches it to the controlling terminal.

I then have an alias for open-session.sh called s so that I can jump into any project with a simple s freebsd or s kyua. These trivial commands surface the existing tmux session for the given project if there is any, or start a new clean session otherwise.

You can find the verbatim contents of my script here:

#! /bin/sh

if [ ${#} -eq 2 ]; then

echo "Provide a session name" 2>&1

exit 1

fi

name=${1}

if tmux list-sessions | grep "^${name}:"; then

tmux attach-session -d -t ${name}

else

case "${name}" in

freebsd) dir=freebsd/base/head ;;

freebsd-10) dir=freebsd/base/stable/10 ;;

netbsd) dir=netbsd/src ;;

ports) dir=freebsd/ports ;;

*) dir="${name}" ;;

esac

if test -d "os/${dir}"; then

( cd "os/${dir}" && DISPLAY= tmux new-session -s ${name} )

else

( DISPLAY= tmux new-session -s "${name}" )

fi

fiSwitching projects

One interesting feature of tmux that I had not yet mentioned is its client/server architecture. The first time you invoke tmux, a background server process is started to manage all tmux sessions. This is a key difference between tmux and Screen, and is an important one.

Once you are within a session, you can jump from one to the other with the Ctrl+J s keybinding. What this means in my setup is that, when I hit those keys, I get a menu with the whole list of projects I currently have open and I can switch back and forth between them at ease within the same terminal window.

Sessions and the terminal emulator

I typically have a single terminal window open at any given time and it is almost always full-screen sitting on its own virtual desktop or monitor (if I happen to have more than one).

Terminal tabs come in handy when I’m moving back and forth two different projects quickly or, more interestingly, when I’m working on projects hosted in different machines. I can have a tab with a local session open for project work and another tab with a remote session on my home server while I do some long-running administration tasks.

Knowing the keybindings to navigate tabs in your terminal emulator is critical. In particular, learn if you can directly switch to a given tab based on its index (Command+Number in OS X, Alt+Number in GTK) and learn how to move to the next and previous tabs as well. Not using the mouse for these operations is critical for efficient work.

What’s within a session?

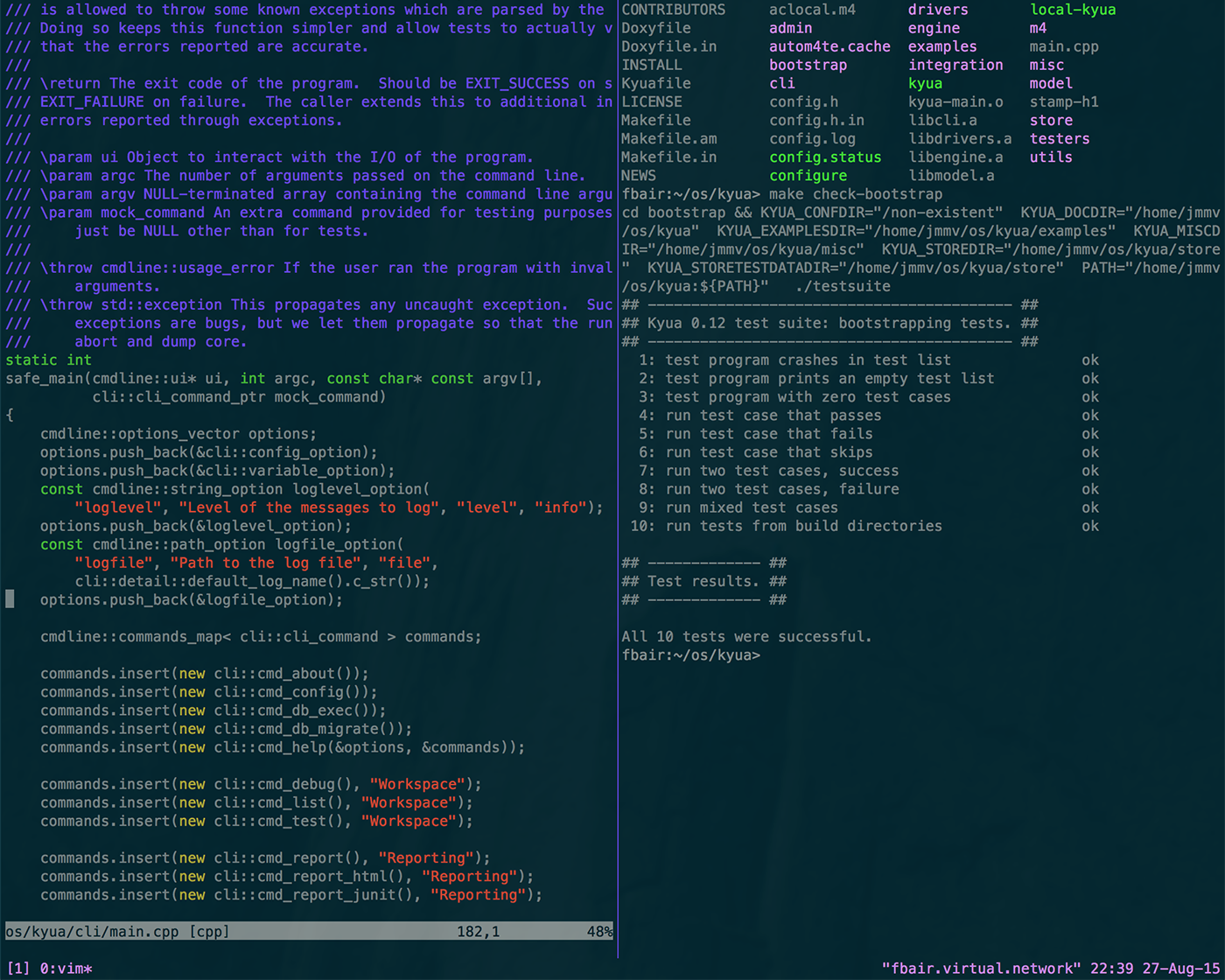

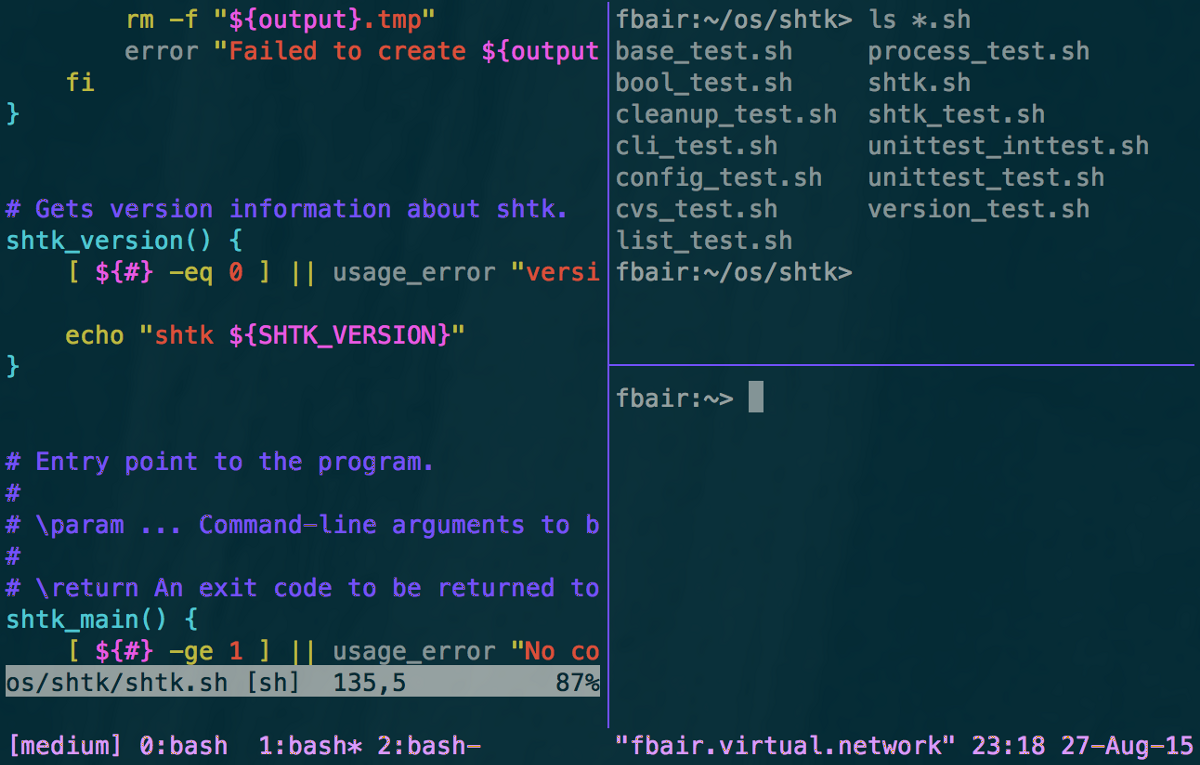

A tmux session holds windows, each window holds one or more panels, and each panel holds a running program.

All my coding sessions follow pretty much the same pattern:

- Window 0 typically is reserved for “scratch” work that does not fit anywhere else. E.g. a quick check on an unrelated project without going through the creation of a new sessions.

- Window 1 is the editing window, and usually holds an Emacs instance running throughout the life of the session. It could also be vim—yes, I use both; no need to argue.

- Window 2 is the compilation and execution window where I just run “make” and “make test”. Sometimes I may also run “make” from within Emacs.

- Window 3, if it exists, is where I may do any other work such as researching stuff, keeping some reference information easily available, or keeping temporary program output for investigation.

For non-coding sessions, such as the session I keep for on-call response, the layout is more unstructured. I tend to run Emacs and compilations in windows 1 and 2 respectively when needed, but if the task at hand does not require neither editing nor building, the windows just get used for anything.

I use tmux’s window splitting—especially vertical splitting, which Screen is not as good at—a lot. Many times, when I’m caught in a fast edit/build/test cycle where I must see the code and the output of the running program side-by-side, I will split Window 1 vertically to keep the editor on the left side and one or two terminal emulators stacked on the right side. Once again, learning the keybindings for window management within tmux is critical for fast operation.

Am I missing out?

Certainly, but should I care?

You’d say I’m missing out for not taking advantage of a graphical environment. For example, Emacs used in graphical mode is much nicer than its console version due to its ability to show many more colors and font faces. Also, once in a graphical environment, there are many more editors to choose from like the now-fashionable Sublime Text or Atom.

You’d also say I’m missing out by relying on a single terminal window when graphical environments are designed to display more than a single tabbed window at once. You might have a point there, but note that tmux’s vertical and horizontal splitting cover this need in pretty much any way. And also note that I did not say I do everything on the console; I have many more graphical apps open at any time to handle email, play music, browse the web, chat, etc.

The “problem” with switching to a different workflow is that I’m now so bought into my own that changing it is almost impossible for the kind of work I currently do. In fact, the work I do now is mostly on remote machines and this workflow happens to fit such needs pretty well.

It will take major changes in my project work types to make me try a new workflow and, when the situation comes, I will openly embrace new ideas. My desire to learn mobile app development may trigger such change because neither Android Studio nor Xcode are console-based, and I cannot fathom writing mobile apps without an IDE.

In short

What to do with your workflow?

- Simply put: do whatever works best for you.

- Do not get too attached to your current workflow. If the circumstances change drastically, consider the possibility of adapting your practices as well because they may not be optimal any longer.

- Keep your eyes open for how other people work; you might be surprised at what you can learn!